Have a Happy and Religious Holiday this Weekend! I will be back Easter morn.

Posted by Jim on April 7, 2023

AOH Home of the Brooklyn Irish

Baile na nGael

Saturday, May 18, 2024

Posted by Jim on April 7, 2023

Posted by Jim on

Dear Sisters & Brothers,

It is with deep sorrow that I inform you of the death of Joan Healey. Joan died yesterday, April 5th, 2023 after a long illness.

Joan was a Degree’d member of LAOH Div. 19 in Gerritsen Beach for over 30 years; she is survived by her husband, AOH Member Jim Healey and is predeceased by her daughter, Mary.

Please stop and say a prayer for Joan and her family.

As Joan goes off to Tir N’ anOg. Tir N’anOg is the place of the Blessed. There is no pain. There is no sorrow. There is only great joy. Weep but briefly for your loved one, for by now Joan has obtained a pleasure that is unattainable on this Earthly Realm. For by now our Sister Joan has seen the face of God. She is at peace.

WAKE:

Marine Park Funeral Home – https://marineparkfh.com/ ,

3024 Quentin Rd, Brooklyn, NY 11234 [Between East 31st Street and Marine Parkway]

VIEWING:

Monday from 4pm – 9pm

MASS:

Tuesday, at 9:45am, Good Shepherd Church- 1950 Batchelder Street, Brooklyn, NY 11229

Yours in Friendship, Unity, and Christian Charity

Mary Hogan

Kings County Secretary

Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Inc

Posted by Jim on April 6, 2023

The Irish Flag

The National Flag of Ireland, often referred to as the tricolour, was first flown 175 years ago this week.

The Irish national flag is a flag of union. Its origin is to be sought in the history of the early nineteenth century and it is emblematic of the fusion of the older elements, represented by the green, with the newer elements, represented by the orange.

The combination of both colours in the tricolour, with the white between in token of brotherhood, symbolises the union of the different stocks in a common nationality.

A green flag with harp was an older symbol used by Irish nationalists, going back at least to Confederate Ireland and Owen Roe O’Neill in the 1640s. It was also widely adopted by the Irish Volunteers in the 1780s and especially by the United Irishmen in the 1798 rebellion.

A rival organisation, the Orange Order, which was exclusively Protestant, was founded in 1795 in memory of King William of Orange and the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1689. Following the 1798 Rebellion, the ideal of a later Nationalist generation in the mid-nineteenth century was to make peace between them and, if possible, to found a self-governing Ireland on such peace and union.

Irish tricolours were mentioned in 1830 and 1844, but widespread recognition was not accorded to the flag until 1848. From March of that year, Irish tricolours appeared side by side with French ones at meetings held all over the country to celebrate the revolution that had just taken place in France. On 7 March 1848, Thomas Francis Meagher, the Young Ireland leader, flew a tricolour from 33 The Mall in Waterford, where it flew continuously for a week until removed by the authorities. On the same day, a tricolour was reported to have been carried in a parade to Vinegar Hill, Enniscorthy, Co Wexford. In April, Meagher brought a tricolour from Paris, presented it to a Dublin meeting and outlined the significance of the colours:

“The white in the centre signifies a lasting truce between Orange and Green and I trust that beneath its folds the hands of Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics may be clasped in generous and heroic brotherhood.”

John Mitchel, also a member of the Young Ireland Movement, said: “I hope to see that flag one day waving as our national banner.”

Although the tricolour was not forgotten as a symbol of hoped-for union and a banner associated with the Young Irelanders and revolution, it was little used between 1848 and 1916. Even up to the eve of the Rising in 1916, the green flag with harp held undisputed sway.

The arrangement of the early tricolours was not standardised. All of the 1848 tricolours showed green, white and orange, but orange was sometimes put next to the staff, and in at least one flag the order was orange, green and white. In 1850 a flag of green for the Catholics, orange for the Protestants of the Established Church and blue for the Presbyterians was proposed. In 1883 a Parnellite tricolour of yellow, white and green, arranged horizontally, is recorded.

Down to modern times yellow or gold has occasionally been used instead of orange, but this substitution destroys the symbolism of the National Flag.

The Irish Tricolour flag was flown over the General Post Office on Easter Monday, 1916, along with a large green flag inscribed with the words “Irish Republic”. The Citizen Army Flag flew on the Imperial Hotel on O’Connell St. during the Rising. This flag shows a stylised representation of a plough with a representation of the constellation Ursa Major superimposed on it, all on a green field bordered by a gilt fringe.

Capturing the national imagination as the banner of the new revolutionary Ireland, the tricolour came to be accepted as the National Flag. It continued to be used officially during the period 1922-1937, and in the latter year its position as the National Flag was formally confirmed by the 1937 Constitution, Article 7 of which states: “The national flag is the tricolour of green, white and orange.”

Posted by Jim on April 5, 2023

Anthony Neeson

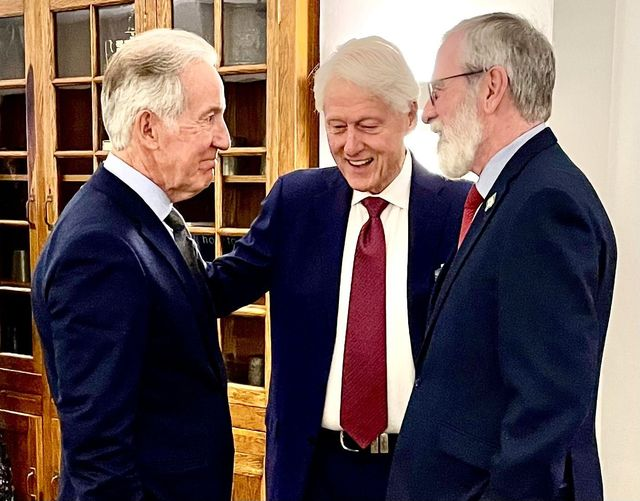

MEETING: Congressman Richard Neal, Gerry Adams and President Bill ClintonMEETING: Congressman Richard Neal, Gerry Adams and President Bill Clinton.

FORMER Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams has welcomed remarks by President Bill Clinton that the Executive and Assembly at Stormont should be restored.

Mr Adams and President Clinton were speaking at an event in New York last night to celebrate 25 years of the Good Friday Agreement. Also in attendance were Friends Of Sinn Féin; Ancient Order of Hibernians; The Friendly Sons of St Patrick; Brehon Law Society; James Connolly Irish American Labor Coalition; and Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Addressing a packed hall in Cooper Union Building Mr Adams said the Good Friday Agreement is the most important political agreement of our time in Ireland.

He said that the results of the last May’s election to the Northern Assembly need to be respected. Sinn Féin were returned as the largest party but an executive hasn’t been formed due to the DUP’s boycott of the institutions over the new Irish Sea post-Brexit trade border.

“If the DUP remain intransigent then the two governments should move ahead using the Good Friday Agreement all-Ireland mechanisms. A return to British direct rule is not an option,” he said.

Commenting on the continuing role of the US Administration Mr Adams added: “We appreciate the work done by President Biden to defend the Good Friday Agreement. People in Ireland still need the White House to act as guarantor of the Agreement, as President Clinton did and as President Biden continues to do.

“And embedded into the Agreement is the right of the people of Ireland to decide our future. It does not belong to an English government or indeed the DUP.”

He added: “The Irish government should establish a Citizen’s Assembly or series of such Assemblies to discuss the process of constitutional change and the measures needed to build an all-Ireland economy, a truly national health service and education system and much more.

“We need national reconciliation in a citizen centred rights based society including the rights of our unionist neighbours – and the Orange Order and other loyal institutions.

The protections in the Good Friday Agreement are their protections also. The island of Ireland is their land, their home place. The unionists are our neighbours. We want them to be our friends. Sinn Féin is committed to upholding their rights and to working with them to make the island of Ireland a better place for everyone.

“The new Ireland planned and built by all of the people of the island can accommodate and celebrate our differences and diversity. Very few countries get the chance to begin anew. Ireland, North and South, has that chance.”

Posted by Jim on March 31, 2023

In the second of three articles, a former adviser to David Trimble recalls the fortnight leading up to the Good Friday Agreement

David Kerr Belfast Telegraph

Today at 01:00

As much as he liked us all, by March 25, 1998, the talks process chairman, Senator George Mitchell, had seen and heard enough. He had spent almost 700 days supervising talks about talks, talks about areas for talks, talks about ceasefires, parties walking out of talks and parties being suspended from talks.

We had made little progress on any substantive issue. Senator Mitchell wanted an outcome, so he announced a hard deadline of Thursday April 9 to reach an agreement, or he was going home.

Deadlines always focus the mind. Nowadays, the veterans of Northern Ireland’s political scene treat them differently. They tell us political negotiations should take as long as they need. Perhaps they should? Or perhaps this rather casual approach, is because the parties now have the benefit of 25 years of relative peace to fall back upon if their negotiations falter?

In 1998, we had no such luxury. If Senator Mitchell’s talks process became yet another failed initiative, in a long litany of failed initiatives stretching back to the early 1970s, we knew violence would follow and many people would lose their lives. We were acutely aware of how highly proficient both sides were in Northern Ireland at bringing misery to each other’s doorsteps.

As we entered the final fortnight of the talks, David Trimble would later quip it was the ‘white knuckle ride’ phase of the negotiations. It most certainly was. All the parties were told to submit their respective ideas and position statements and the UK Government, through Senator Mitchell, would aim to produce a working draft document by Friday April 3.

While the UUP and SDLP talked regularly and to both Governments, the UUP refused to speak to Sinn Fein.

The UUP couldn’t work out whether the IRA was committed to peace and a settlement. We knew there were major internal divisions within republicanism. Could Sinn Fein really sign up to the principle of consent? Could Adams convince them to support a devolution and partitionist settlement, when Sinn Fein had declared in September 1997, at the opening round of the ‘Strand 1’ talks (about the internal governance of Northern Ireland), that there would be ‘No return to Stormont’?

The truth is no-one knew what they could accept, and at that stage if they couldn’t support an Agreement, as far as we were concerned, that was their problem.

As a veteran of the failed political initiatives of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, David Trimble knew the price of failure for unionism and Northern Ireland. His sole focus was on getting the constitutional architecture of any deal right.

He wanted to banish the ghosts of Sunningdale and ensure that any North-South cooperation would be accountable to a new Stormont Assembly.

He wanted Stormont restored, the principle of consent accepted by all, and the territorial claim over Northern Ireland in Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Republic’s constitution removed.

Within the two loyalist parties in the talks as we entered that final week, there was quiet support for Trimble’s approach. If the complex constitutional aspects of the deal were good enough for the UUP legal experts, they would support it.

The strategic concern of the UUP and the loyalist parties was that if the talks collapsed, Tony Blair would cut a deal with the Irish Government in an Anglo-Irish Agreement Mark II, with no gains for unionism and most likely, hidden concessions to Sinn Fein.

Friday April 3

We had expected to receive a comprehensive final draft version of the Agreement on April 3, but it didn’t arrive.

Senator Mitchell had been told by the Governments to delay while they continued to work on the document. The UUP team feared the worst — that the Irish would be busy inserting their wish-list into the document. We would later learn that Sinn Fein had told the Irish that if the Strand 2 (North-South institutions) section of the deal was substantive enough, the IRA would declare a permanent ceasefire.

Monday April 6

When the draft agreement finally arrived on April 6, David Trimble split the document into sections to be analysed by specialist sub-groups within the UUP talks team covering Strand 1, Strand 2 and Strand 3.

The UUP team took seconds to conclude that the Strand 2 section was completely unacceptable. It had three annexes, with annex A covering 25 areas for immediate cooperation, annex B setting out 16 areas and a further eight areas in annex C.

Worse still, the structures were independent meaning no accountability to Stormont, and that if devolution failed in Northern Ireland, the North-South structures would carry on regardless.

Trimble was furious. Senator Mitchell was almost apologetic to him, as we would later learn, he had warned the Governments that he knew the UUP wouldn’t accept it.

Sensing disaster that evening, John Alderdice, then leader of the Alliance Party, would famously say outside Castle Buildings to the assembled media, ‘If the Prime Minister wants a deal, he’d better get over here fast’.

Tuesday April 7

As we arrived back to Castle Buildings on the Tuesday, the UUP talks team was still examining the overall draft agreement. David Trimble was concerned about the proposal for an independent commission on policing, but his attitude remained, the document would have to be changed and the UUP would not walk away without a fight to get a deal secured.

Senator Mitchell told Trimble that Tony Blair was trying to get changes to Strand 2 but the Irish were refusing to budge. Trimble phoned the Prime Minister to underline our problems with Strand 2 and he asked Blair to come over and take charge of the situation.

The Prime Minister and his entourage would subsequently fly to Northern Ireland and base themselves at Hillsborough Castle, where that evening, in front of the assembled TV cameras, Tony Blair would feel the infamous ‘hand of history on his shoulder’.

David Trimble was invited to Hillsborough to meet the PM that evening where, over dinner, they talked in detail for two hours about the draft agreement.

Meanwhile, back at Castle Buildings, UUP deputy leader John Taylor was in charge and following another internal meeting to discuss the draft document, I was dispatched upstairs to tell Senator Mitchell that we were now publicly rejecting the deal.

In all my time during the talks, I don’t think I ever saw anyone look so visibly stressed as Senator Mitchell looked as I delivered this message.

In his typically flamboyant manner, Taylor would leave that evening to attend a function in London telling the assembled media, he ‘wouldn’t touch the draft document with a 40ft barge pole’.

Whilst all of this political drama was being played out in Belfast, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern was dealing with a profoundly more distressing and personal tragedy — the death of his mother.

He had been keeping vigil beside her since she had passed away on the Sunday night, from a heart attack. Her funeral was to take place on Wednesday afternoon.

Following the formal and very public rejection of the draft deal by the UUP, the message was sent to Ahern that unless something was done, the talks would collapse.

Wednesday April 8

To his eternal credit in the circumstances, on the morning of his mother’s funeral, Bertie Ahern flew to Belfast around 6.30am to meet with the UUP to discuss the problems with Strand 2. He spoke to Tony Blair and then flew back to Dublin for his mother’s burial.

He would then return to Castle Buildings that evening, to take personal charge of the Strand 2 negotiations. As he arrived back and walked past me in the corridor, he looked as I expected him to look — awful.

When I delivered the message to our team, that he was back, we knew he wanted to get a deal done.

The UUP and Irish Government would negotiate late in the early hours of Thursday morning to eventually agree a completely revised Strand 2 agreement. Three annexes were reduced to one, which set out 12 defined areas for co-operation to be discussed and agreed by Stormont.

They would not be described as ‘Executive’ bodies. A unionist minister would have to be present at all North/South Ministerial Council meetings to approve decisions.

The UUP had successfully banished the mistakes of Sunningdale. Trimble was delighted.

We would later learn that Sinn Fein were so outraged about this, they threatened to walk out, but with promises on prisoners from both Governments and their own political shopping list of some 60 items, Sinn Fein would choose to stay.

Thursday April 9

As we arrived back at Castle Buildings on the Thursday morning, the focus had shifted to the other parts of the Agreement. Intensive talks between the SDLP and UUP centred around Strand 1 matters, which basically concerned the format of a Stormont Assembly and a possible Executive.

As far as we were aware, despite the UUP having never met Sinn Fein during the talks process in a bi-lateral format, Sinn Fein had not taken part in any of the discussions for Strand 1.

They were certainly true to their ‘No return to Stormont’ mantra — and it gives a clear indication of how far they would subsequently travel by signing up to the Good Friday Agreement.

There were approximately 38 drafts of the Strand 1 papers and the UUP and SDLP did pretty much all of the negotiating between themselves.

The UUP Strand 1 team was led by Reg Empey. He had initially proposed the Welsh model or ‘Committee system’ as it was known.

The UUP calculation was that this would avoid the political drama of Sinn Fein holding Ministerial positions, as Committee chairs could be rotated between MLAs, much the same as they do on councils around Northern Ireland.

Viewed through the prism of 2023, it would be easy to misrepresent this approach as exclusionary. But the UUP team at that point simply felt it was a bridge too far for the unionist electorate to accept a Sinn Fein Minister in a devolved Government — especially if there was no evidence the ‘war’ was over or decommissioning would take place.

It’s also worth noting that even 25 years after the Good Friday Agreement, both Fine Gael and Fianna Fail still refuse to share power with Sinn Fein in Dublin.

The UUP would eventually agree to an Executive and Assembly structure, as a better form of Government, especially when promoting Northern Ireland to an international audience.

The UUP negotiators felt they had secured their constitutional objectives on Strand 2, so they needed to come to an agreement with the SDLP, who wanted an Executive structure.

Strand 1 was eventually signed off late on the Thursday night with the SDLP.

David Trimble would say afterwards that he thought John Hume was going to burst into tears. As the meeting concluded, Hume embraced John Taylor in a moment of profound symbolism between the UUP and SDLP.

Talks had been proceeding on various issues in parallel to this, such as Strand 3 (East-West structures) and the long talked about concept of a British Irish Council (BIC).

The BIC was intended to give unionists the equivalent institutional dimension to the Strand 2 North/South Ministerial Council. It would bring together the various devolved Governments of the UK, Ireland, the Isle of man and Channel Islands in a unique forum, to discuss matters of mutual interest and cooperation.

As the clock moved towards 6pm on the Thursday evening, David Trimble had another engagement to attend — a meeting of his 110 member ruling UUP Executive, in Glengall Street. He had promised to brief them before any deal was agreed at Stormont.

The meeting was scheduled for 6.30pm. We still hadn’t agreed anything on policing, prisoners or decommissioning and time was running out.

The next 24 hours would turn out to be the most important — and arguably career defining — for everyone in the UUP talks team.

Senator Mitchell had wanted a deal agreed before Good Friday, but he was going to have to wait a bit longer.

The concluding article of this three-part series will focus on the final 24 hours of the talks that led to the Good Friday Agreement on April 10, 1998. It will be published on Good Friday (April 7), ahead of the agreement’s 25th anniversary.