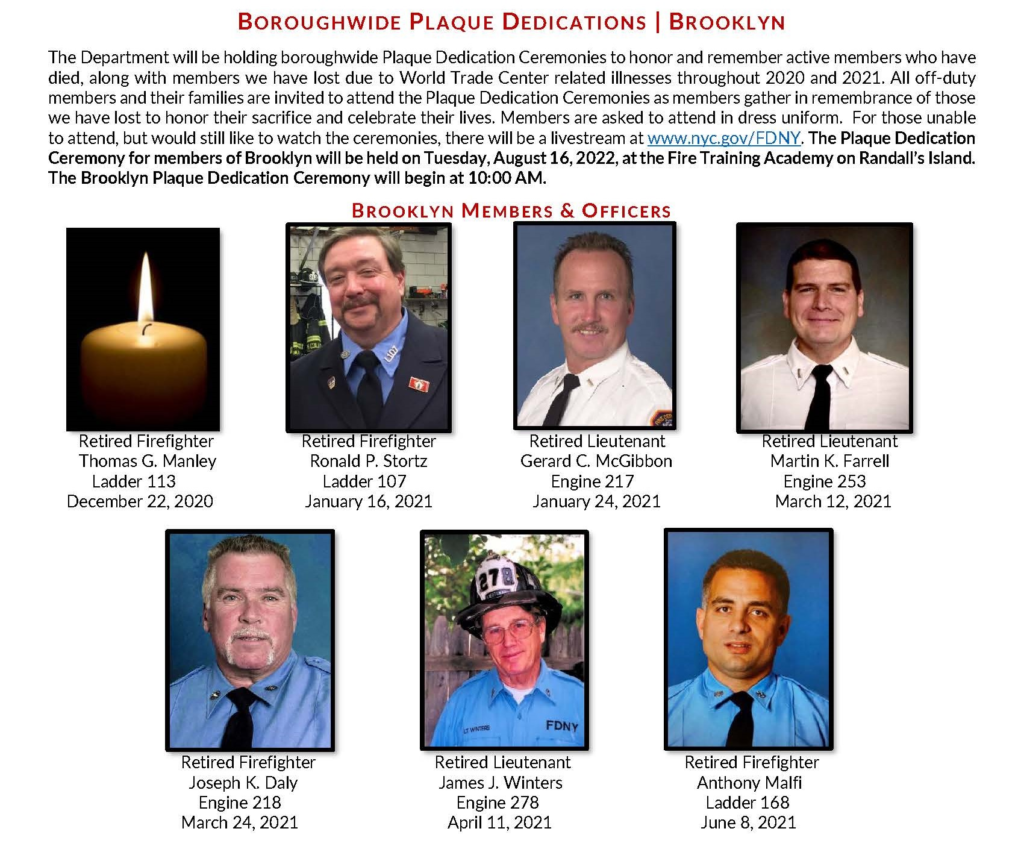

Boroughwide Plaque Dedications Brooklyn

Posted by Jim on August 10, 2022

“Forever Rats” 249/113, take up Tommy, you deserve some R n R. You’ll always be in our hearts.

God bless the FDNY!

AOH Home of the Brooklyn Irish

Baile na nGael

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Posted by Jim on August 10, 2022

“Forever Rats” 249/113, take up Tommy, you deserve some R n R. You’ll always be in our hearts.

God bless the FDNY!

Posted by Jim on August 9, 2022

https://youtube.com/watch?v=tfhgNuql_hk%3Fautoplay%3D1

On Monday 9th of August 1971 Interment Without Trial was introduced by the British Government in the North of Ireland. This policy was implemented by the British Army at 4am on that particular summer morning. The British Army directed the campaign against the predominately Catholic community with the stated aim to “shock and stun the civilian population”.

Between 9th and 11th of August 1971, over 600 British soldiers entered the Ballymurphy area of West Belfast, raiding homes and rounding up men. Many, both young and old, were shot and beaten as they were dragged from their homes without reason. During this 3 day period 11 people were brutally murdered.

All 11 unarmed civilians were murdered by the British Army’s Parachute Regiment. One of the victims was a well known parish priest and another was a 45 year old mother of eight children. No investigations were carried out and no member of the British Army was held to account.

It is believed that some of the soldiers involved in Ballymurphy went on to Derry some months later where similar events occurred. Had those involved in Ballymurphy been held to account, the events of Bloody Sunday may not have happened.

The terrible events which took place in Ballymurphy in 1971 have for too long remained in the shadows. Here we, the families of those murdered, put the spotlight on how 11 innocent people met their deaths over a three day period in August 1971.

The Massacre – Chronology

9th August 1971

On the 9th of August 1971, at roughly 8:30pm, in the Springfield Park area of West Belfast, a local man was trying to lift children to safety when he was shot and wounded by the British Army’s Parachute Regiment. Local people tried to help the wounded man but were pinned back by the Parachute Regiment’s gunfire. Local parish priest, Father Hugh Mullan, telephoned the Henry Taggart army post to tell them he was going into the field to help the injured man.

Father Mullan entered the field, waving a white baby grow. He anointed the injured man, named locally as Bobby Clarke. Having identified that Bobby had received a flesh wound and was not fatally wounded, Father Mullan attempted to leave the field. At this point Father Mullan was fatally shot in the back.

On witnessing such events another young man of 19 years, Frank Quinn, came out of his place of safety to help Father Mullan. Frank was shot in the back of the head as he tried to reach Father Mullan. The bodies of Father Hugh Mullan and Frank Quinn lay where they were shot until local people could safely reach them. Their bodies remained in neighbouring homes until they could be safely removed the next morning.

Tension was rising in the community as local youths fought back against the army’s horrendous campaign. Families were fleeing their homes in Springfield park as they came under attack from loyalist mobs approaching from the direction of Springmartin. Parents frantically searched for their children. Local men were still being removed from their homes, beaten and interned without reason. All this and at the same time the people of Ballymurphy were trying to live a normal life.

Local people had started gathering at the bottom of Springfield Park, an area known locally as the Manse. Some of those gathering included Joseph Murphy who was returning from the wake of a local boy who drowned in a swimming accident. Joan Connolly and her neighbour Anna Breen stopped as they searched for their daughters. Daniel Teggart also stopped as he returned from his brother’s house which was close to Springfield Park. Daniel had gone to his brother’s house to check on his brother’s safety as his house had been attacked as local youth targeted the Henry Taggart Army base located near by. Noel Phillips, a young man of 19 years, having just finished work walked to Springfield park to check on the local situation.

Without warning the British Army opened fire from the direct of the Henry Taggart Army base. The shooting was aimed directly at the gathering. In the panic people dispersed in all directions. Many people took refuge in a field directly opposite the army base. The army continued to fire and intensified their attack on this field.

Noel Phillips was shot in the back side. An injury that was later described in his autopsy as a flesh wound. As he lay crying for help, Joan Connolly, a mother of 8 went to his aid. Eye witnesses heard Joan call out to Noel saying “It’s alright son, I’m coming to you”.

In her attempt to aid Noel, Joan was shot in the face. When the gun fire stopped Noel Phillips, Joan Connolly, Joseph Murphy and many others lay wounded. Daniel Teggart, a father of 14, lay dead having been shot 14 times.

A short time later a British Army vehicle left the Henry Taggart Army base and entered the field. A solider exited the vehicle, and to the dismay of the local eye witnesses, executed the already wounded Noel Phillips by shooting him once behind each ear with a hand gun.

Soldiers then began lifting the wounded and dead and throwing them into the back of the vehicle. Joseph Murphy, who had been shot once in the leg, was also lifted along with the other victims and taken to the Henry Taggart Army base. Those lifted, including Joseph Murphy, were severely beaten. Soldiers brutally punched and kicked the victims. Soldiers jumped off bunks on top of victims and aggravated the victims’ existing wounds by forcing objects in to them. Mr Murphy was shot at close range with a rubber bullet into the wound he first received in the field. Mr Murphy died three weeks later from his injuries.

Joan Connolly, who had not been lifted by the soldiers when they first entered the field, lay wounded where she had been shot. Eye witnesses claimed Joan cried out for help for many hours. Joan was eventually removed from the field around 2:30am on 10th August. Autopsy reports state that Joan, having been repeatedly shot and bled to death.

10th August 1971

Eddie Doherty, a father of two from the St James’ area of West Belfast, had visited his elderly parents in the Turf Lodge area, on the evening of Tuesday 10th August to check on their safety during the ongoing unrest. He was making his way home along the Whiterock road, as he approached the West Rock area he noticed a barricade which had been erected by local people in an attempt to restrict access to the British Army.

A local man named Billy Whelan, known to Eddie, stopped him and the pair passed commented on the ongoing trouble. At the same time a British Army digger and Saracen moved in to dismantle the barricade. From the digger, a soldier from the Parachute Regiment opened fire. Eddie was fatally shot in the back. Local people carried him to neighbouring homes in an attempt to provide medical attention but Eddie died a short time later from a single gun shot wound.

11th August 1971

At roughly 4am on 11th August. John Laverty, a local man of 20 years, was shot and killed by soldiers from the British Army’s Parachute regiment. Joseph Corr, a local father of 6, was also shot and wounded by the same regiment. Mr Corr died of his injuries 16 days later. The Parachute Regiment’s account stated that both men were firing at the army and were killed as the army responded. Neither men were armed and ballistic and forensic evidence tested at the time disproved the army’s testimony.

Pat McCarthy, a local community worker who came to work in Ballymurphy from England, was shot in the hand on the same day as he was attempting to leave the local community centre to distribute milk and bread to neighbouring families. A few hours later and nursing his wounded hand, Pat decided to continue with the deliveries. He was stopped by soldiers from the British Army’s Parachute Regiment who harassed and beat him.

Eye witness’ watched in horror as the soldiers carried out a mock execution on Pat by placing a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger, only for the gun to be unloaded. Pat suffered a massive heart attack and the same soldiers stopped local people from trying to help Pat. As a result Pat died from the ordeal.

John McKerr, a father of 8 and a carpenter from the Andersonstown Road area, was carrying out repair work in Corpus Christi chapel on the 11th August. John took a short break to allow the funeral of a local boy, who drowned in a swimming accident, to take place. As he waited outside the chapel for the funeral mass to end, John was shot once in the head by a British solider from the Army’s Parachute Regiment.

Despite the harassment of the British Army, local people went to his aid and remained at his side until an ambulance arrived. One local woman, named locally as Maureen Heath, argued with the soldiers as they refused to allow John to be taken in the ambulance. John was eventually taken to hospital but died of his injuries 9 days later having never regained consciousness.

Posted by Jim on

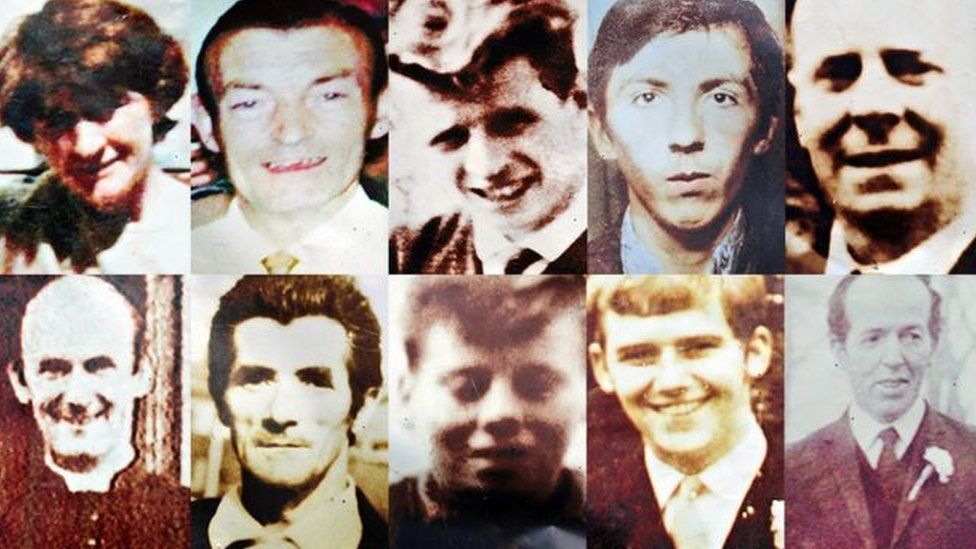

Families of those killed in Ballymurphy in west Belfast 51 years ago have marked the anniversary of their deaths.

Ten people, including a mother of eight and a Catholic priest, were shot over three days in August 1971.

In 2021 a coroner at the inquest into the deaths found found the victims were entirely innocent of any wrongdoing.

A relative of one of those killed said that ruling had made this year’s memorial “so different”.

In June it was announced that the families of some of those killed in Ballymurphy were to receive significant undisclosed damages.

The 1971 killings immediately followed the introduction of internment – the arrest and detention of paramilitary suspects without trial.

Speaking after Sunday’s parade Eileen McKeown, the daughter of victim Joseph Corr, said this year’s march was poignant.

“When we do this every year we are fighting for justice and for this year to be saying that they’re innocent, that we proved our loved ones to be innocent just feels so different.

“The atmosphere is different,” she told BBC News NI.

“You know you don’t have the fight that we had beforehand ahead of us,” she added.

John Teggart’s father, Daniel, was among those killed in the series of shootings between 9 August and 11 August.

He voiced his opposition to the controversial Northern Ireland Troubles Bill, which is aimed at ending Troubles legacy prosecutions.

“We are still marching and giving a voice to other victims,” he said.

“There is work to be done. We need to be mobilizing, back on the streets and counteract what the Tories intend to bring in and this bill of shame- we hope to stop it in its tracks,” he added.

Posted by Jim on August 5, 2022

Posted by Jim on August 4, 2022

An essay written by Bobby Sands in 1979 while protesting against the criminalisation of republican prisoners. Because protesting prisoners were not allowed books or writing materials, this essay was composed on a square of toilet paper and smuggled out of the prison.

My grandfather once said that the imprisonment of the lark is a crime of the greatest cruelty because the lark is one of the greatest symbols of freedom and happiness. He often spoke of the spirit of the lark relating to a story of a man who incarcerated one of his loved friends in a small cage.

The lark, having suffered the loss of her liberty, no longer sung her little heart out, she no longer had anything to be happy about. The man who had committed the atrocity, as my grandfather called it, demanded that the lark should do as he wished: that was to sing her heart out, to comply to his wishes and change herself to suit his pleasure or benefit.

The lark refused, and the man became angry and violent. He began to pressurise the lark to sing, but inevitably he received no result. so, he took more drastic steps. He covered the cage with a black cloth, depriving the bird of sunlight. He starved it and left it to rot in a dirty cage, but the bird still refused to yield. The man murdered it.

As my grandfather rightly stated, the lark had spirit – the spirit of freedom and resistance. It longed to be free, and died before it would conform to the tyrant who tried to change it with torture and imprisonment. I feel I have something in common with that bird and her torture, imprisonment and final murder. She had a spirit which is not commonly found, even among us so-called superior beings, humans.

Take an ordinary prisoner. His main aim is to make his period of imprisonment as easy and as comfortable as possible. The ordinary prisoner will in no way jeopardise a single day of his remission. Some will even grovel, crawl and inform on other prisoners to safeguard themselves or to speed up their release. They will comply to the wishes of their captors, and unlike the lark, they will sing when told to and jump high when told to move.

Although the ordinary prisoner has lost his liberty he is not prepared to go to extremes to regain it, nor to protect his humanity. He settles for a short date of release. Eventually, if incarcerated long enough, he becomes institutionalised, becoming a type of machine, not thinking for himself, his captors dominating and controlling him. That was the intended fate of the lark in my grandfather’s story; but the lark needed no changing, nor did it wish to change, and died making that point.

This brings me directly back to my own situation: I feel something in common with that poor bird. My position is in total contrast to that of an ordinary conforming prisoner: I too am a political prisoner, a freedom fighter. Like the lark, I too have fought for my freedom, not only in captivity, where I now languish, but also while on the outside, where my country is held captive. I have been captured and imprisoned, but, like the lark, I too have seen the outside of the wire cage.

I am now in H-Block, where I refuse to change to suit the people who oppress, torture and imprison me, and who wish to dehumanise me. Like the lark I need no changing. It is my political ideology and principles that my captors wish to change. They have suppressed my body and attacked my dignity. If I were an ordinary prisoner they would pay little, if any, attention to me, knowing that I would conform to their insitutional whims.

I have lost over two years’ remission. I care not. I have been stripped of my clothes and locked in a dirty, empty cell, where I have been starved, beaten, and tortured, and like the lark I fear I may eventually be murdered. But, dare I say it, similar to my little friend, I have the spirit of freedom that cannot be quenched by even the most horrendous treatment. Of course I can be murdered, but while I remain alive, I remain what I am, a political prisoner of war, and no one can change that.

Haven’t we plenty of larks to prove that? Our history is heart-breakingly littered with them: the MacSwineys, the Gaughans, and the Staggs. Will there be more in H-Block?

I dare not conclude without finishing my grandfather’s story. I once asked him whatever happened to the wicked man who imprisoned, tortured and murdered the lark?

‘Son,” he said, ‘one day he caught himself on one of his own traps, and no one would assist him to get free. His own people scorned him, and turned their backs on him. He grew weaker and weaker, and finally topled over to die upon the land which he had marred with such blood. The birds came and extracted their revenge by picking his eyes out, and the larks sang like they never sang before.’

‘Grandfather,’ I said, ‘could that man’s name have been John Bull?’