Nationalists should have taken Winston Churchill’s advice on Irish unity

Posted by Jim on January 19, 2025

Sam McBride

Today at 07:17

As the quintessential embodiment of British defiance, Winston Churchill may be an unlikely inspiration for Irish nationalists. His support for Home Rule notwithstanding, Britain’s wartime leader — who died 60 years ago this week — was the antithesis of many of the values espoused by those seeking Irish self-determination.

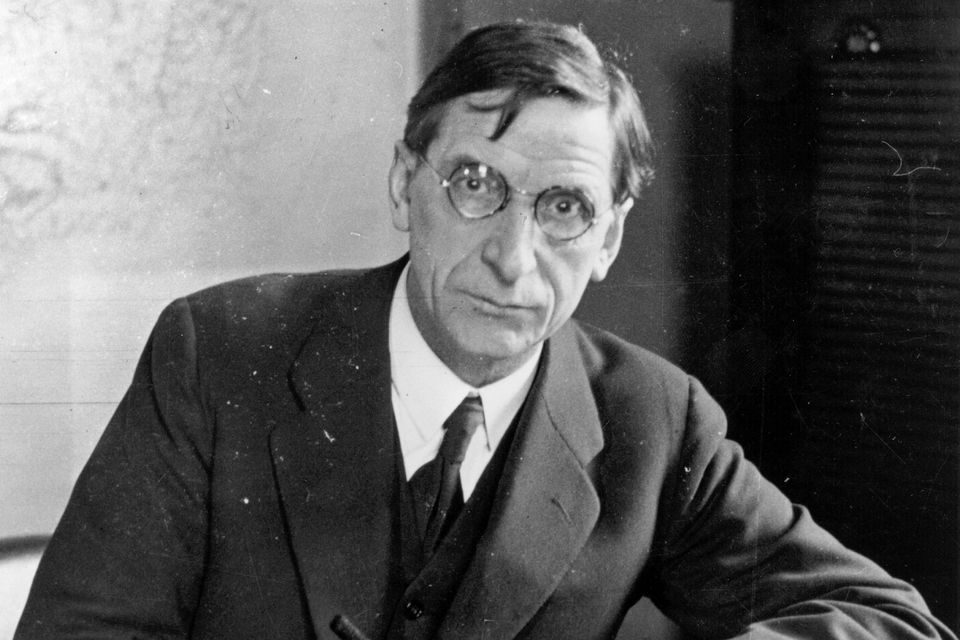

Yet this imperialist and militarist, so uncompromising in his exterior and at times ferociously critical of Éamon de Valera’s fledgling new state, repeatedly gave advice which, if Irish nationalists had followed it, would have made Irish unity far more likely.

The crux of that advice — to kill unionists with kindness rather than threatening them — is now official Irish Government policy as expressed in the Shared Island Unit which is throwing cash at projects in Northern Ireland to build reconciliation, the Republic’s constitutional claim on the six counties now long in the past.

Indeed, so gentle is the Shared Island Unit’s approach that a critical aspect of its decision-making on projects is whether they would make sense even if the Border is never removed.

As with so many of the great political questions of his era, Churchill’s view of Ireland was open to alteration

For those who want to see both sides of the island flourish, regardless of the constitutional arrangements which pertain, this is eminently sensible. But it wasn’t always seen as common sense to lavish warmth on what were seen as recalcitrant northern unionists.

As with so many of the great political questions of his era, Churchill’s view of Ireland was open to alteration.

Writing in 1896 as a 21-year-old, the future prime minister privately said he would “never consent” to home rule for Ireland. Yet, just over a decade later he was spearheading that policy.

He would be involved not only in negotiating the Anglo-Irish Treaty but in attempting to build social relationships between James Craig and Michael Collins away from the talks.

Churchill’s ability to bombastically argue both sides of most debates provides ample material for dispute between those who say he was lacking in political principle and those who view him as someone who would abandon past positions out of sincere belief that circumstances had changed rather than out of a craven desire for personal advancement.

What is strikingly consistent, however, across shifting decades and circumstances, was Churchill’s sadness that partition had endured and his desire to see the eventual removal of the Border.

For someone who not only espoused Empire but had taken part in some of its wars, he was clear-eyed about British sins in Ireland. Writing in 1896 to his American friend Bourke Cockran — a Sligo-born lawyer to whom he later attributed his oratorical skill — he acknowledged past atrocities, saying: “I consider it unjust to arraign the deeds of earlier times before modern tribunals and to judge by modern standards. No one denies — no one has ever attempted to deny — that England has treated Ireland disgracefully in the past.

“Those were hard times; death was the punishment of every crime and the treatment of the Irish by the stronger power was in harmony with the treatment of the French peasantry, the Russian serfs and the Hugenots.”

However, by 1912 when he famously enraged Ulster unionists by coming to Belfast to defend home rule, he told an audience in Celtic Park: “History and poetry, justice and good sense alike demand that this race — gifted, virtuous and brave, which has lived so long and endured so much should not, in view of her passionate desire, be shut out of the family of nations and should not be lost forever among indiscriminate multitudes of men.”

Although De Valera’s covert assistance to the allies is now far better understood, Irish neutrality during World War II enraged Churchill. In a 1945 victory address to the nation, he raged against “the action of Mr de Valera, so much at variance with the temper and instinct of thousands of southern Irishmen, who hastened to the battlefront to prove their ancient valour”, saying “if it had not been for the loyalty and friendship of Northern Ireland we should have been forced to come to close quarters with Mr de Valera or perish forever from the earth”.

Yet just after that flash of anger came a very different sentiment: “When I think of these days I think also of other episodes and personalities. I do not forget Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde, VC, DSO, Lance-Corporal Kenneally, VC, Captain Fegen, VC, and other Irish heroes that I could easily recite, and all bitterness by Britain for the Irish race dies in my heart. I can only pray that in years which I shall not see the shame will be forgotten and the glories will endure, and that the peoples of the British Isles and of the British Commonwealth of Nations will walk together in mutual comprehension and forgiveness.”

Three years later, he said: “It seemed to me that the passage of time might lead to the unity of Ireland itself in the only way in which that unity can be achieved, namely, by a union of Irish hearts. There can, of course, be no question of coercing Ulster, but if she were wooed and won of her own free will and consent I, personally, would regard such an event as a blessing for the whole of the British Empire and also for the civilised world.”

Yet the remarkable element of Churchill’s view about how unity might come about wasn’t that it was especially inventive or insightful but that it was so obvious

Richard Pim, an Ulsterman who was on Churchill’s personal staff as head of his map room during the war, recalled a 1942 lunch between Lloyd George, Stormont prime minister JM Andrews and Churchill in which the trio proceeded “with the assistance of wine glasses, salt and pepperpots, to discuss in detail the Irish question in 1900”. He recalled Churchill and Lloyd George said they wouldn’t under any circumstances “permit the coercion of Ulster in the future. At the same time, both made it very clear that they still entertained the hope that in the future some statesman would rise in Ulster who would feel justified in making a move towards closer harmony with the south.”

They hoped for a correspondingly farsighted southern interlocutor who could smooth “harmony with Northern Ireland”. But their reasons weren’t wholly selfless: “They believed that if such a change of heart was to be found in the North and in the south, then the North, because of the history of its ancestors, would automatically become the real controller of the new Ireland, which she would bring again fully within the folds of the British Empire.”

There are elements of this which were delusional as the Empire was fading away. Yet the remarkable element of Churchill’s view about how unity might come about wasn’t that it was especially inventive or insightful but that it was so obvious — yet so alien to the time.