Francis Hughes – Died on 12 May 1981 on hunger strike in the H-Blocks

Posted by Jim on May 12, 2020

• Fearless and tenacious guerrilla fighter Volunteer Francis Hughes

» Special Correspondent

THE DEATH of Francis Hughes at the age of 25 on hunger strike in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh saw not the end of a legend but a new chapter in what was, by any measure, the story of one of the most fearless and tenacious guerrilla fighters of the 20th Century and of the Irish Republican Army.

Born in Bellaghy, South Derry, on 28 February 1956, Francis was once described by the British authorities as “the most wanted man” in the North of Ireland – a telling indication of his effectiveness as a guerrilla fighter against enemy forces in his native terrain.

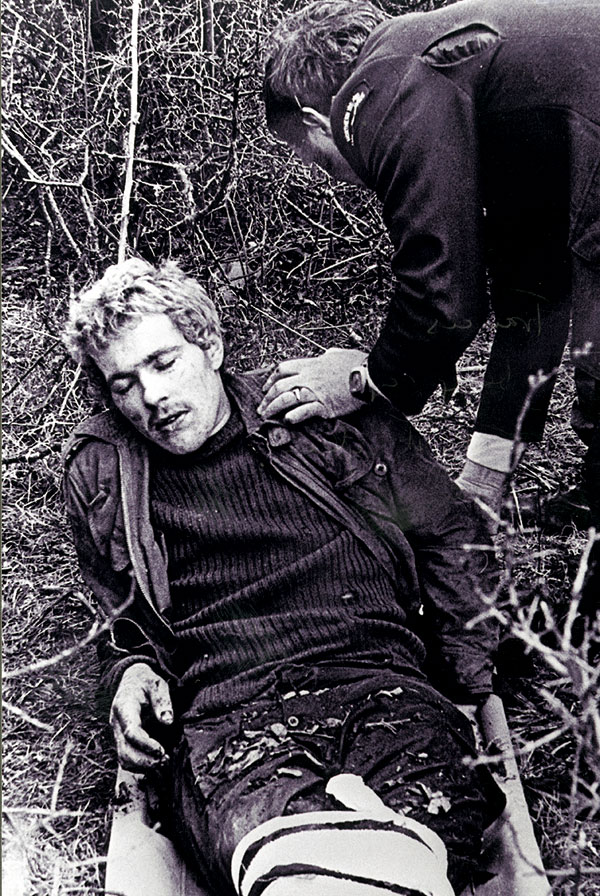

He was arrested on 16 March 1978 following a gun battle in which an undercover British soldier was killed. Francis was seriously wounded during the exchange and was captured in a follow-up search of the area. He received a life sentence in February 1980.

Francis Hughes died on 12 May 1981 after 59 days on hunger strike.

Legendary Volunteer dies on Hunger Strike

• Legendary freedom fighter Francis Hughes, pictured during his capture by crown forces. Hughes lies badly injured following a gun battle. He wears combat clothing and his hair has been dyed to disguise his identity

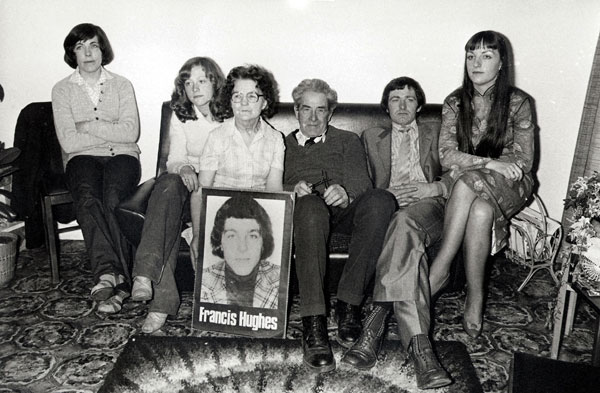

ON 12 May 1981, at 5:43 pm, just seven days after the death of Bobby Sands, Hunger Striker Francis Hughes died. The South Derry man had endured 59 days on hunger strike. His sisters Noreen, Maria and Vera and brother Roger were by his bedside when he passed away.

Paying tribute to Hughes, the IRA said he was one of the bravest soldiers of the armed struggle against British rule.

Sinn Féin’s Gerry Adams called on British Premier Margaret Thatcher to accept that her efforts to stare down the Hunger Strike had failed, and for Taoiseach Charles Haughey to end his silence, which Adams said encouraged British intransigence.

Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich implored of Thatcher:

“How many more Irishmen must go to their graves inside and outside before intransigence gives way to a constructive effort to find a solution?”

In the United States, Senator Edward Kennedy decried Thatcher’s intransigence whilst Boston City Council renamed the street on which the British Consulate is located as Francis Hughes Street.

Speaking to An Phoblacht on the day before his son’s death, Francis Hughes’s father told of his last visit to his dying son:

“It’s a terrible thing to see a young lad dying but amazingly he was in great spirits. His face was just yellow with eyes sunken. Just the same as a corpse lying there. I said: ‘Do you see me, Francis?’ He said: ‘I see the shape of you but I can’t see your face.’

“When he had gotten a wee sleep he chatted away and caught my hand and held it tight. I said to him, ‘You’re not too bad,’ and he said, ‘Ah, now, tomorrow or Wednesday will see the end of it.’”

• The Hughes family

Reaction on the streets

The evening of Francis Hughes’s death saw an upsurge in attacks by the IRA with the British Army and RUC coming under fire across Belfast. Riots, which had been raging since the death of Bobby Sands, intensified with nationalist youths across the Six Counties engaging British crown forces with bricks and petrol bombs.

In Dublin, the most serious rioting since the 1972 burning of the British Embassy in the aftermath of the Bloody Sunday massacre of civil rights marchers by British paratroopers occurred. Gardaí attacked a march going from the GPO to the British Embassy in Ballsbridge with an indiscriminate baton charge.

Sinn Féin President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh castigated Taoiseach Charles Haughey on his inaction.

On the same evening, in a sickening and deliberate act of murder, 14-year-old Julie Livingston was killed by a British Army plastic bullet in Lenadoon, west Belfast. Francis Hughes’s death was the impetus for an increased use of lethal plastic bullets and injuries received from them rose dramatically across the Six Counties after 12 May.

Legendary figure

Francis Hughes had been captured by the British on 16 March 1978 following a gun battle that killed an SAS soldier and left Hughes wounded in the leg.

He had been branded the North’s most wanted man by the RUC and was a legendary figure in his native south Derry and beyond. He had become involved in the armed struggle after witnessing the brutality of crown forces and experiencing it first-hand with harassment and beatings.

He had participated in the 1980 Hunger Strike and in 1981 he volunteered again and was accepted. In an open letter he wrote to the people of south Derry about his decision to go on hunger strike:

“I have no prouder boast than to say I am Irish and have been privileged to fight for the Irish people and for Ireland. If I have a duty I will perform it to the full with the unshakeable belief that we are a noble race and that chains and bonds have no part in us.”

He was a cousin of Thomas McElwee who would also die on the 1981 Hunger Strike.

• Volunteers of Óglaigh na hÉireann fire a volley in salute to their deceased comrade

Funeral

In death, the legendary south Derry volunteer instilled as much fear amongst crown forces as he had in life. The RUC hijacked his funeral cortege to prevent it passing through west Belfast on its sad return to County Derry. An RUC man was observed spitting on the coffin.

At the funeral, there were poignant scenes as Francis Hughes’s father, Joseph, approached an RUC cordon barring access to Bellaghy. His appeal to be allowed bring his son to St Mary’s Church fell on deaf ears and the cortege was forced to take a circuitous route. Earlier, the IRA had bid farewell to their comrade with a volley of shots over his Tricolour-draped coffin outside the Hughes family home.

The funeral was marked by a day of mourning with businesses in nationalist areas shutting down and vigils and rallies occurring the length and breadth of the country. There were also numerous rallies abroad.

Chairing the graveside ceremony was south Derry republican John Davey, a friend of Francis Hughes, who was later murdered by a pro-British death squad. The graveside oration was delivered by Martin McGuinness.

Addressing a crowd of thousands, McGuinness paid tribute to the bravery of Francis Hughes, both as an active IRA Volunteer and as a political prisoner and a hunger striker. Outlining the history of the Blanket Protest and its escalation into the hunger strikes he rejected British propaganda that sought to portray republicans as sectarian and the IRA as criminals. McGuinness went on to say that the Hunger Strike had challenged the political and religious leadership of the country and they had been found wanting. John Hume and Charles Haughey had been whipped into line by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, he said.

Concluding with a moving tribute to Francis Hughes, Martin McGuinness said:

“His body lies here beside us but he lives in the little streets of Belfast; he lives in the Bogside; he lives in East Tyrone; he lives in Crossmaglen. He will always live in the hearts and minds of unconquerable Irish republicans in all these places. They could not break him. They will not break us.”

• A crowd of thousands at the funeral heard Martin McGuinness declare of Francis Hughes: ‘They could not break him. They will not break us’