Louise Sullivan LAOH State of Florida President

Posted by Jim on February 1, 2023

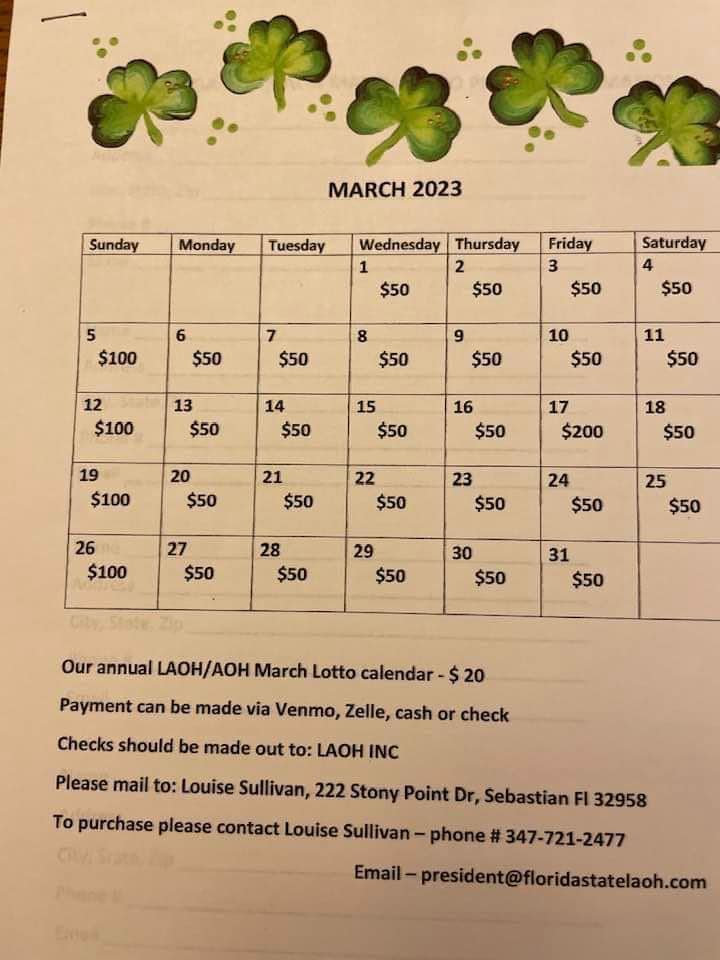

March will be here before you know it! Get your calendar now and play lotto with us. For $20 you are in the game with 31 chances to win cash prizes each day.

AOH Home of the Brooklyn Irish

Baile na nGael

Thursday, April 18, 2024

Posted by Jim on February 1, 2023

March will be here before you know it! Get your calendar now and play lotto with us. For $20 you are in the game with 31 chances to win cash prizes each day.

Posted by Jim on January 31, 2023

David Young, Rebecca Black and Jonathan McCambridge, PA

31 January, 2023 14:24

Victims’ campaigners have urged the EU to “stand up” to the UK in opposing controversial laws to deal with the legacy of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

Bereaved relatives called on the EU for support and also asked MEPs to hold a debate in the European Parliament and pass a resolution criticising the Government’s proposed legislative changes.

The Legacy Bill, which is going through its parliamentary stages at Westminster, would see a form of immunity offered to those suspected of killings during the conflict if they agree to co-operate with a new truth recovery body.

It would also prohibit future civil cases and inquests related to Troubles crimes.

It has been almost universally opposed by parties across the political divide in Northern Ireland, as well as all victims’ groups. The Irish Government is also opposed to the plan.

The Government has proposed several amendments to the Bill as it proceeds through its legislative stages, though the core elements of it remain.

A film about a number of killings during the Troubles in Northern Ireland was shown to a gathering of MEPs in Brussels on Tuesday.

It came on the same day the Legacy Bill was back on the parliamentary schedule in London for further consideration in the House of Lords.

The film, made by Mobile Media and the Truth and Justice Movement, features eight people who have lost family members in a number of atrocities, including the Omagh bomb, the Ballymurphy massacre and Bloody Sunday.

It has already been shown to parliamentarians at Westminster, members of the Oireachtas parliament in Dublin and Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris.

Victims’ campaigner Raymond McCord, who attended the screening was part of a campaign of opposition to the UK Government’s controversial plans to deal with the legacy of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

Mr McCord, whose son Raymond Jnr was killed by loyalist paramilitaries in 1997, said the European Parliament had a reputation for supporting justice and human rights.

“We ask for this shameful legacy/amnesty bill of human rights abuse and cover-up, along with the violation of truth and justice, to be debated in the EU parliament,” he said.

“We ask to speak in front of the 705 MEPs who have been elected to make Europe a better and safer place with equality and human rights for all.

“We need not only a resolution from the EU parliament with full support for our group and victims in total rejection of this bill and the betrayal of victims and justice, we also need the EU to stand up to a British government that has no regard for truth and justice and deals it signs.”

Mr McCord said 3,600 deaths in the Troubles would equate to 1.2 million deaths among the population of the EU.

“Unlike the British government, please stand with us, the victims not the murderers,” he urged MEPs.

“Remember the children blown up with bombs and shot in the head, the women raped and murdered, men and women murdered in front of their families, men lined up and riddled with bullets, the sectarian murder gangs and imagine if it was your own son, daughter or mother or father being buried in a closed coffin because of their horrific injuries.

“This film clearly shows the pain and injustice inflicted on thousands of victims.

“Who are those in this EU parliament who believes that murder is a crime unlike what this Bill proposes?

“Who are those in this EU parliament see justice as paramount to democracy?

“Our murdered family members must be respected by the EU parliament by rejecting this Bill not only in this parliament but in the European courts.

“We believe that not one MEP would support this Bill.

“Whether it’s one murder or 3,600 murders, the EU parliament has a choice, solidarity with victims or complicit in washing their hands of truth, justice and human rights.

“No sectarian agenda, no political agenda, only truth and justice.”

Irish MEP Frances Fitzgerald said: “This is a hugely important and heartbreaking film which gives voice to the trauma of the families of some of those murdered during the Troubles, on both sides.

“It shows how important it is to speak up in opposition to the proposals before the UK Parliament, which would prevent the perpetrators from being prosecuted.

“Such a proposal is outrageous and devastating for families seeking justice.

“The Irish Government and all parties in Leinster House have been very clear in their opposition to this proposed legislation.

“Now this campaign is coming to the European Parliament and I encourage all my colleagues from all member states to come and see the film and show their support for the campaigners.”

Irish senator Emer Currie praised the victims for bringing their campaign to Brussels.

“This is a really important day for victims,” she said.

“They continue to grow their campaign against the Legacy Bill, which has been criticised and condemned by everyone from the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights and Council of Europe Committee of Members to members of US Congress.

“Today the victims bring their personal and powerful stories of loss and trauma to the European Parliament, with the message that international human rights obligations must be upheld and we all have a role in ensuring that.”

Posted by Jim on January 30, 2023

The Troubles

Bloody Sunday, or the Bogside Massacre,[1] was a massacre on 30 January 1972 when British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march in the Bogside area of Derry, [n 1] Northern Ireland. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers, and some were shot while trying to help the wounded.[2] Other protesters were injured by shrapnel, rubber bullets, or batons, two were run down by British Army vehicles, and some were beaten.[3][4] All of those shot were Catholics. The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) to protest against internment without trial. The soldiers were from the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (“1 Para”), the same battalion implicated in the Ballymurphy massacre several months before.[5]

Two investigations were held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the aftermath, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame. It described some of the soldiers’ shooting as “bordering on the reckless” but accepted their claims that they shot at gunmen and bomb-throwers. The report was widely criticised as a “whitewash”.[6][7][8] The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the incident much more thoroughly. Following a twelve-year investigation, Saville’s report was made public in 2010 and concluded that the killings were “unjustified” and “unjustifiable”. It found that all of those shot were unarmed, that none were posing a serious threat, that no bombs were thrown and that soldiers “knowingly put forward false accounts” to justify their firing.[9][10] The soldiers denied shooting the named victims but also denied shooting anyone by mistake.[11] On publication of the report, British Prime Minister David Cameron formally apologised.[12] Following this, police began a murder investigation into the killings. One former soldier was charged with murder, but the case was dropped two years later when evidence was deemed inadmissible.[13] Following an appeal by the families of the victims, however, the Public Prosecution Service resumed the prosecution.

Bloody Sunday came to be regarded as one of the most significant events of the Troubles because so many civilians were killed by forces of the state, in view of the public and the press.[1] It was the highest number of people killed in a shooting incident during the conflict and is considered the worst mass shooting in Northern Irish history.[15] Bloody Sunday fuelled Catholic and Irish nationalist hostility to the British Army and worsened the conflict. Support for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) rose, and there was a surge of recruitment into the organisation, especially locally.[16] The Republic of Ireland held a national day of mourning, and huge crowds besieged and burnt down the British Embassy in Dublin.

Background

Main article: The Troubles

The City of Derry was perceived by many Catholics and Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland to be the epitome of what was described as “fifty years of Unionist misrule”: despite having a nationalist majority, gerrymandering ensured elections to the City Corporation always returned a unionist majority. The city was perceived to be deprived of public investment: motorways were not extended to it, a university was opened in the smaller (Protestant-majority) town of Coleraine rather than Derry and, above all, the city’s housing stock was in a generally poor state.[17][page needed] Derry therefore became a major focus of the civil rights campaign led by organisations such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in the late 1960s. It was the scene of the major riot known as Battle of the Bogside in August 1969, which pushed the Northern Ireland administration to ask for military support.[18]

While many Catholics initially welcomed the British Army as a neutral force – in contrast to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), which was regarded as a sectarian police force – relations between them soon deteriorated.[19]

In response to rising levels of violence across Northern Ireland, internment without trial was introduced on 9 August 1971.[20] There was disorder across the region following the introduction of internment, with 21 people being killed in three days of violence.[21] In Belfast, soldiers of the Parachute Regiment shot dead eleven civilians in what became known as the Ballymurphy Massacre.[5] On 10 August, Bombardier Paul Challenor became the first soldier to be killed by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA) in Derry, when he was shot by a sniper in the Creggan housing estate.[22] A month after internment was introduced, a British soldier shot dead 14-year-old Catholic schoolgirl Annette McGavigan in Derry.[23][24] Two months later, Kathleen Thompson, a 47-year-old mother of six was shot dead in her back garden in Derry by the British Army.[25][26]

IRA activity also increased across Northern Ireland, with thirty British soldiers being killed in the remaining months of 1971, in contrast to the ten soldiers killed during the pre-internment period of the year.[21] A further six soldiers had been killed in Derry by end of 1971.[27] At least 1,332 rounds were fired at the British Army, who also faced 211 explosions and 180 nail bombs,[27] and who fired 364 rounds in return. Both the ‘Provisional’ IRA and the ‘Official’ IRA had built barricades and established no-go areas for the British Army and RUC in Derry.[28] By the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to prevent access to what was known as Free Derry, sixteen of them impassable even to the British Army’s one-ton armoured vehicles.[28] IRA members openly mounted roadblocks in front of the media, and daily clashes took place between nationalist youths and the British Army at a spot known as “aggro corner”.[28] Due to rioting and incendiary devices, an estimated £4 million worth of damage had been caused to local businesses.[28]

Lead-up to the march

On 18 January 1972 the Northern Irish Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner, banned all parades and marches in the region until the end of the year.[29] Four days later, in defiance of the ban, an anti-internment march was held at Magilligan strand, near Derry. Protesters marched to an internment camp but were stopped by soldiers of the Parachute Regiment. When some protesters threw stones and tried to go around the barbed wire, paratroopers drove them back by firing rubber bullets at close range and making baton charges. The paratroopers badly beat a number of protesters and had to be physically restrained by their own officers. These allegations of brutality by paratroopers were reported widely on television and in the press. Some in the British Army also thought there had been undue violence by the paratroopers.[30][31]

NICRA intended to hold another anti-internment march in Derry on 30 January. The authorities decided to allow it to proceed in the Bogside, but to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square, as planned by the organisers, to avoid rioting. Major General Robert Ford, then Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, ordered that the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment (1 Para), should travel to Derry to be used to arrest rioters.[32] The arrest operation was codenamed ‘Operation Forecast’.[33] The Saville Report criticised Ford for choosing the Parachute Regiment for the operation, as it had “a reputation for using excessive physical violence”.[34] March organiser and MP Ivan Cooper had been promised beforehand that no armed IRA members would be near the march, although Tony Geraghty wrote that some of the stewards were probably IRA members.[35]

Events of the day

Main article: Narrative of events of Bloody Sunday (1972)

The paratroopers arrived in Derry on the morning of the march and took up positions.[36] Brigadier Pat MacLellan was the operational commander and issued orders from Ebrington Barracks. He gave orders to Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford, commander of 1 Para. He in turn gave orders to Major Ted Loden, who commanded the company who would launch the arrest operation. The protesters planned on marching from Bishop’s Field, in the Creggan housing estate, to the Guildhall in the city centre, where they would hold a rally. The march set off at about 2:45 p.m. There were 10,000–15,000 people on the march, with many joining along its route.[37] Lord Widgery, in his now discredited tribunal,[38][39][40][41] said that there were only 3,000 to 5,000.[42]

The march made its way along William Street but, as it neared the city centre, its path was blocked by British Army barriers. The organisers redirected the march down Rossville Street, intending to hold the rally at Free Derry Corner instead. However, some broke off from the march and began throwing stones at soldiers manning the barriers. The soldiers fired rubber bullets, CS gas and water cannons.[43] Such clashes between soldiers and youths were common, and observers reported that the rioting was no more violent than usual.[44]

Some of the crowd spotted paratroopers occupying a derelict three-story building overlooking William Street, and began throwing stones up at the windows. At about 3:55 p.m., these paratroopers opened fire. Civilians Damien Donaghy and John Johnston were shot and wounded while standing on waste ground opposite the building. These were the first shots fired.[45] The soldiers claimed Donaghy was holding a black cylindrical object,[46] but the Saville Inquiry concluded that all of those shot were unarmed.[47]

At 4:07 p.m., the paratroopers were ordered to go through the barriers and arrest rioters. The paratroopers, on foot and in armoured vehicles, chased people down Rossville Street and into the Bogside. Two people were knocked down by the vehicles. MacLellan had ordered that only one company of paratroopers be sent through the barriers, on foot, and that they should not chase people down Rossville Street. Wilford disobeyed this order, which meant there was no separation between rioters and peaceful marchers.[48] There were many claims of paratroopers beating people, clubbing them with rifle butts, firing rubber bullets at them from close range, making threats to kill, and hurling abuse. The Saville Report agreed that soldiers “used excessive force when arresting people […] as well as seriously assaulting them for no good reason while in their custody”.[49]

One group of paratroopers took up position at a low wall about 80 yards (73 m) in front of a rubble barricade that stretched across Rossville Street. There were people at the barricade and some were throwing stones at the soldiers, but were not near enough to hit them.[50] The soldiers fired on the people at the barricade, killing six and wounding a seventh.[51]

A large group of people fled or were chased into the car park of Rossville Flats. This area was like a courtyard, surrounded on three sides by high-rise flats. The soldiers opened fire, killing one civilian and wounding six others.[52] This fatality, Jackie Duddy, was running alongside a priest, Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back.[2]

Another group of people fled into the car park of Glenfada Park, which was also surrounded by flats. Here, the soldiers shot at people across the car park, about 40–50 yards (35–45 m) away. Two civilians were killed and at least four others wounded.[53] The Saville Report says it is probable that at least one soldier fired randomly at the crowd from the hip.[54] The paratroopers went through the car park and out the other side. Some soldiers went out the southwest corner, where they shot dead two civilians. The other soldiers went out the southeast corner and shot four more civilians, killing two.[55]

About ten minutes had elapsed between the time soldiers drove into the Bogside and the time the last of the civilians was shot.[56] More than 100 rounds were fired by the soldiers.[57] No warnings were given before soldiers opened fire.[11]

Some of those shot were given first aid by civilian volunteers, either on the scene or after being carried into nearby homes. They were then driven to hospital, either in civilian cars or in ambulances. The first ambulances arrived at 4:28 p.m. The three boys killed at the rubble barricade were driven to hospital by paratroopers. Witnesses said paratroopers lifted the bodies by the hands and feet and dumped them in the back of their armoured personnel carrier as if they were “pieces of meat”. The Saville Report agreed that this is an “accurate description of what happened”, saying the paratroopers “might well have felt themselves at risk, but in our view this does not excuse them”.[58]

Casualties

In all, 26 people were shot by the paratroopers;[3][2] thirteen died on the day and another died of his injuries four months later. The dead were killed in four main areas: the rubble barricade across Rossville Street, the car park of Rossville Flats (on the north side of the flats), the forecourt of Rossville Flats (on the south side), and the car park of Glenfada Park.[2]

All of the soldiers responsible insisted that they had shot at, and hit, gunmen or bomb-throwers. No soldier said he missed his target and hit someone else by mistake. The Saville Report concluded that all of those shot were unarmed and that none were posing a serious threat. It also concluded that none of the soldiers fired in response to attacks, or threatened attacks, by gunmen or bomb-throwers.[11]

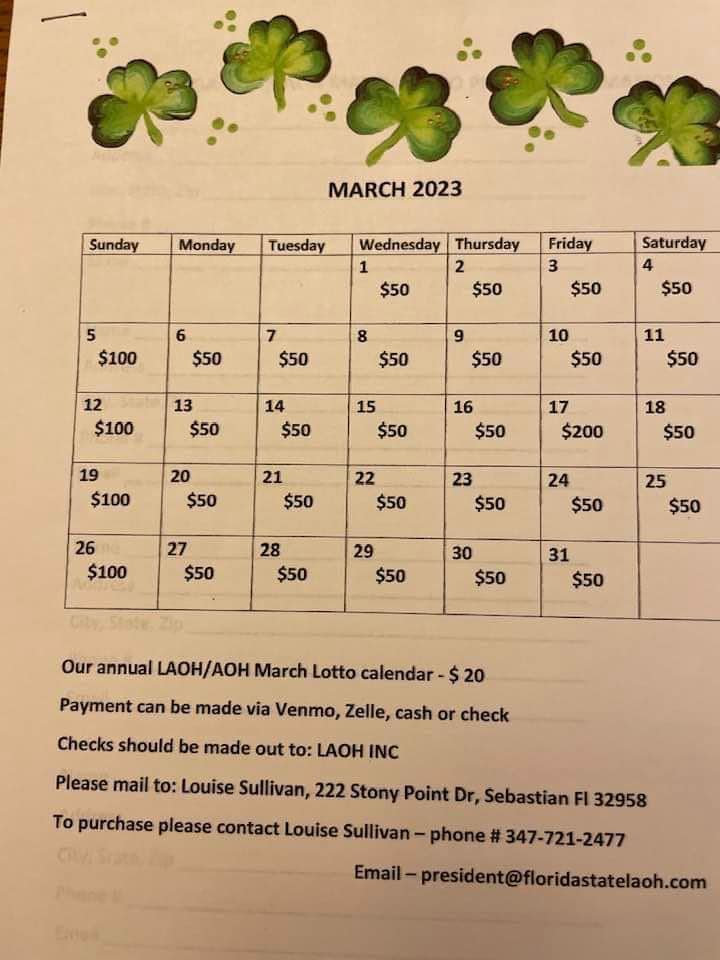

The casualties are listed in the order in which they were killed.

John “Jackie” Duddy, age 17. Shot as he ran away from soldiers in the car park of Rossville Flats.[2] The bullet struck him in the shoulder and entered his chest. Three witnesses said they saw a soldier take deliberate aim at the youth as he ran.[2] He was the first fatality on Bloody Sunday.[2] Both Saville and Widgery concluded that Duddy was unarmed.[2]

Michael Kelly, age 17. Shot in the stomach while standing at the rubble barricade on Rossville Street. Both Saville and Widgery concluded that Kelly was unarmed.[2] The Saville Inquiry concluded that ‘Soldier F’ shot Kelly.[2]

Hugh Gilmour, age 17. Shot as he ran away from soldiers near the rubble barricade.[2] The bullet went through his left elbow and entered his chest.[59] Widgery acknowledged that a photograph taken seconds after Gilmour was hit[60] corroborated witness reports that he was unarmed.[61] The Saville Inquiry concluded that ‘Private U’ shot Gilmour.[2]

William Nash, age 19. Shot in the chest at the rubble barricade.[2] Three people were shot while apparently going to his aid, including his father Alexander Nash.[62]

John Young, age 17. Shot in the face at the rubble barricade, apparently while crouching and going to the aid of William Nash.[62]

Michael McDaid, age 20. Shot in the face at the rubble barricade, apparently while crouching and going to the aid of William Nash.[62]

Kevin McElhinney, age 17. Shot from behind, near the rubble barricade, while attempting to crawl to safety.[2]

James “Jim” Wray, age 22. Shot in the back while running away from soldiers in Glenfada Park courtyard. He was then shot again in the back as he lay mortally wounded on the ground. Witnesses, who were not called to the Widgery Tribunal, stated that Wray was calling out that he could not move his legs before he was shot the second time. The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by ‘Soldier F’.[2]

William McKinney, age 26. Shot in the back as he attempted to flee through Glenfada Park courtyard.[63] The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by ‘Soldier F’.[2]

Gerard “Gerry” McKinney, age 35. Shot in the chest at Abbey Park. A soldier, identified as ‘Private G’, ran through an alleyway from Glenfada Park and shot him from a few yards away. Witnesses said that when he saw the soldier, McKinney stopped and held up his arms, shouting, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!”, before being shot. The bullet apparently went through his body and struck Gerard Donaghy behind him.[2]

Gerard “Gerry” Donaghy, age 17. Shot in the stomach at Abbey Park while standing behind Gerard McKinney. Both were apparently struck by the same bullet. Bystanders brought Donaghy to a nearby house. A doctor examined him, and his pockets were searched for identification. Two bystanders then attempted to drive Donaghy to hospital, but the car was stopped at a British Army checkpoint. They were ordered to leave the car and a soldier drove it to a Regimental Aid Post, where an Army medical officer pronounced Donaghy dead. Shortly after, soldiers found four nail bombs in his pockets. The civilians who searched him, the soldier who drove him to the Army post, and the Army medical officer all said that they did not see any bombs. This led to claims that soldiers planted the bombs on Donaghy to justify the killings. [n 2]

Patrick Doherty, age 31. Shot from behind while attempting to crawl to safety in the forecourt of Rossville Flats. The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by ‘Soldier F’, who came out of Glenfada Park.[2] Doherty was photographed, moments before and after he died, by French journalist Gilles Peress. Despite testimony from ‘Soldier F’ that he had shot a man holding a pistol, Widgery acknowledged that the photographs show Doherty was unarmed, and that forensic tests on his hands for gunshot residue proved negative.[2][67]

Bernard “Barney” McGuigan, age 41. Shot in the back of the head when he walked out from cover to help Patrick Doherty. He had been waving a white handkerchief to indicate his peaceful intentions.[61][2] The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by ‘Soldier F’.[2]

John Johnston, age 59. Shot in the leg and left shoulder on William Street fifteen minutes before the rest of the shooting started.[2][68] Johnston was not on the march, but on his way to visit a friend in Glenfada Park.[68] He died on 16 June 1972; his death has been attributed to the injuries he received on the day. He was the only fatality not to die immediately or soon after being shot.[2]

Aftermath

Thirteen people were shot and killed, with another wounded man dying subsequently, which his family believed was from injuries suffered that day.[69] Apart from the soldiers, all eyewitnesses—including marchers, local residents, and British and Irish journalists present—maintain that soldiers fired into an unarmed crowd, or were aiming at fleeing people and those helping the wounded. No British soldier was wounded by gunfire or bombs, nor were any bullets or nail bombs recovered to back up their claims.[57] The British Army’s version of events, outlined by the Ministry of Defence and repeated by Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in the House of Commons the day after Bloody Sunday, was that paratroopers returned fire at gunmen and bomb-throwers.[70] Bernadette Devlin, the independent Irish socialist republican Member of Parliament (MP) for Mid Ulster, slapped Maudling for his comments,[71] and was temporarily suspended from Parliament.[72] Having seen the shootings firsthand, she was infuriated that the Speaker of the House of Commons, Selwyn Lloyd, repeatedly denied her the chance to speak about it in Parliament, although convention decreed that any MP witnessing an incident under discussion would be allowed to do so.[73][74]

On Wednesday 2 February 1972, tens of thousands attended the funerals of eleven of the victims.[75] In the Republic of Ireland it was observed as a national day of mourning, and there was a general strike, the biggest in Europe since the Second World War relative to population.[76] Memorial services were held in Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as synagogues, throughout the Republic, while schools closed and public transport stopped running. Large crowds had been besieging the British embassy on Merrion Square in Dublin, and embassy staff had been evacuated. That Wednesday, tens of thousands of protesters marched to the embassy and thirteen symbolic coffins were placed outside the entrance. The Union Jack was burnt and the building was attacked with stones and petrol bombs. The outnumbered Gardaí tried to push back the crowd, but the embassy was burnt down.[77] Anglo-Irish relations hit one of their lowest ebbs with the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Patrick Hillery, going to the United Nations Security Council to demand the involvement of a UN peacekeeping force in the Northern Ireland conflict.[78] Kieran Conway, the head of the IRA’s intelligence-gathering department for a period in the 1970s, stated in his memoir that after the massacre, the IRA Southern Command in Dublin received up to 200 applications from Southern Irish citizens to fight the British.[79]

Harold Wilson, then the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Commons, reiterated his belief that a united Ireland was the only possible solution to Northern Ireland’s Troubles.[80] William Craig, then Stormont Home Affairs Minister, suggested that the west bank of Derry should be ceded to the Republic of Ireland.[81]

On 22 February 1972, the ‘Official’ IRA attempted to retaliate for Bloody Sunday by detonating a car bomb at Aldershot military barracks, headquarters of 16th Parachute Brigade, killing seven ancillary staff.[75]

An inquest into the deaths was held in August 1973. The city’s coroner, Hubert O’Neill, a retired British Army major, issued a statement at the completion of the inquest. He declared:

This Sunday became known as Bloody Sunday and bloody it was. It was quite unnecessary. It strikes me that the Army ran amok that day and shot without thinking what they were doing. They were shooting innocent people. These people may have been taking part in a march that was banned but that does not justify the troops coming in and firing live rounds indiscriminately. I would say without hesitation that it was sheer, unadulterated murder. It was murder.[75]

Posted by Jim on

Jan 28, 2023

A “No Irish Need Apply” sign.

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem are widely regarded as one of Ireland’s greatest-ever ballad groups and their cover of the 19th-century ballad “No Irish Need Apply” tells the story of anti-Irish discrimination in the United States.

Written in 1862, the song tells the story of an Irish immigrant who faces outward discrimination in his search for a job on the grounds that he is Irish.

The immigrant is faced with a sign bearing the slogan “No Irish Need Apply” (NINA), causing his temper and sense of injustice to rise. He argues with the business owner responsible for the slogan, reasoning that their ancestors also emigrated to America and were welcomed with open arms but is unsuccessful in his attempts to gain employment.

Unperturbed, the Irish immigrant notes that the business owner is one of a few “bad apples” that persevere with anti-Irish prejudices and that most employers would be happy to hire an Irishman.

The song is rooted in anti-Irish sentiment in America and Britain throughout the 19th century.

In America, Catholic Irish immigrants faced discrimination from nativists, often facing NINA signs when looking for work, with a significant amount of discrimination coming from Irish and English Protestants living in the United States.

Irish Catholics were largely marginalized in mid-19th century American society, with future President Theodore Roosevelt describing them as a “stupid, sodden and vicious lot, most of them being equally deficient in brains and virtue”.

In Britain, Irish immigrants faced similar discrimination and prejudice and were regularly faced with NINA signs. The rampant anti-Irish discrimination in Britain gave rise to the first known versions of the famous song, with two editions making their way across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States.

In one version of the song, the immigrant faces discrimination in London and emigrates to America to escape the anti-Irish prejudice in the Land of the Free.

In another, the immigrant still faces discrimination in America despite fleeing London.

It was the latter version of the song that became popular among Irish immigrants in the United States, popularizing the idea that the Irish community faced NINA signs no matter where they turned in search of employment.

That theory has been questioned by some scholars, like American historian Dr. Richard Jensen of the University of Illinois, who claimed that No Irish Need Apply was nothing more than a “myth of victimization”.

Jensen claimed that there was no significant discrimination against the Irish in the job market in America, but his argument was rebutted by Rebecca Fried, an eighth-grader from Washington DC.

Fried found that there was plenty of evidence that disproved Jensen’s argument and proved that there was a significant amount of discrimination against Irish immigrants looking for work in 19th-century America.

Despite Jensen’s protestations, it seems as though NINA signs really did exist on a tangible level in America as they did in Britain, giving rise to the famous song.

Posted by Jim on January 28, 2023

By Jimmy Murphy

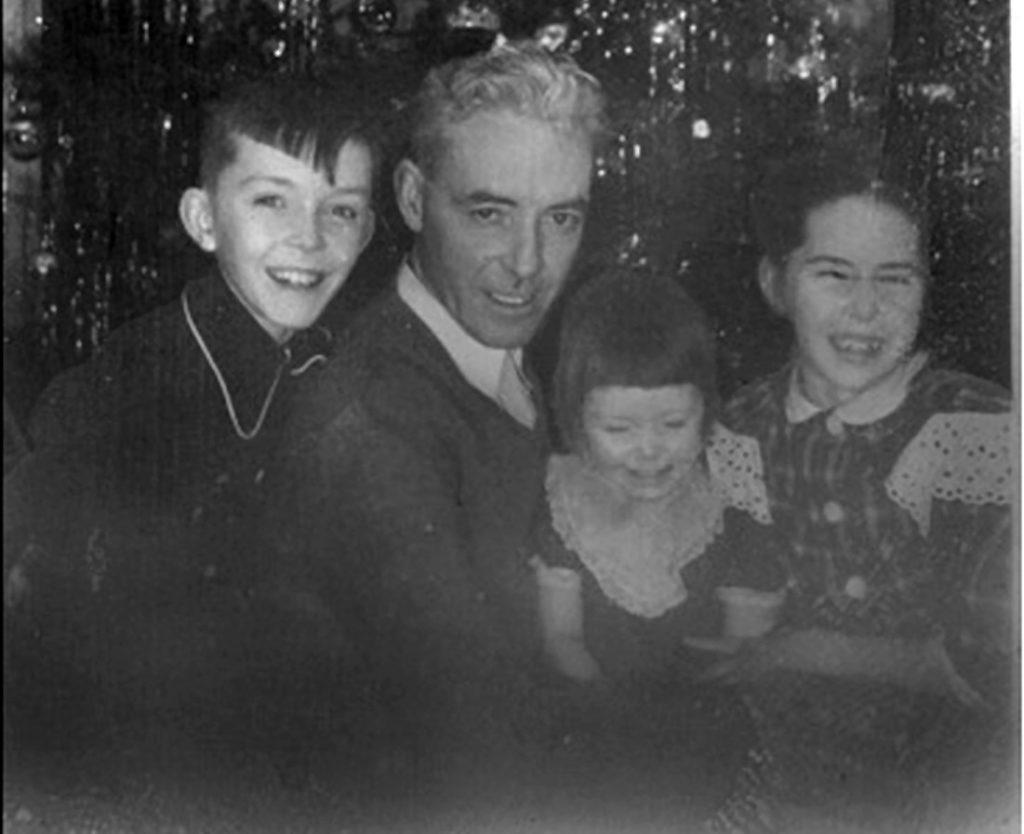

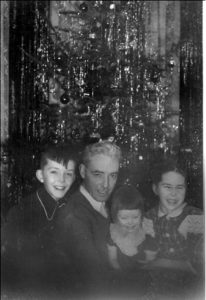

Jimmy, Eileen, and Joan with their dad, Patrick “Joe” Murphy on Christmas Day, 1948. Photo courtesy of Jim Murphy

In the Brooklyn world of my childhood, Ireland seemed especially close at Christmas. While we kids looked forward to Santa, Mom and Dad were looking back to Ireland. Cards would arrive, and Mom would cherish each and every one, especially those from her sisters, my Aunts Una and Joan, who would include letters for her to linger over, her eyes growing all teary. My parents left home in the 1920s – Mom at age 16 from Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo, and Dad at 21 from Cloone, Co. Leitrim. They met in an Irish dance hall in Manhattan, courted, married, and worked hard to keep our family of five afloat. They are both long gone now, but each year at Christmas, I hear their voices again.

One Christmas was so much like another in those years that they now all blur into one big ball of holidays. Let me pick one sometime in the late 1940s: our apartment on Newkirk Avenue is alive with expectation because today we will bring home our tree. It’s sure to be a fine big tree because each year Dad helps Paddy Power sell trees after Sunday mass at St. Jerome’s Church on Nostrand Avenue.

“Prime location, that’s the key,” Dad says. “The subway and church are right there so there’s lots of traffic. After mass people are feeling good about things and they know you’re one of their own since you’re there at the church and Paddy is an usher.Sure you couldn’t keep the man out of church, so naturally he gets the business instead of some huckster who might not even be a Christian. There’s no flies on Paddy Power, that’s for sure. He knows where his bread is buttered and, fair play to him, he’s there all year with the ushering so why shouldn’t he pick up a few dollars when the time comes? I must say, selling trees to a crowd spilling out of church is ‘easy pickins,’ as your man would say.”

On Sundays leading up to Christmas, the streets are alive with families and trees moving in all directions. Sometimes a father would throw one up on his shoulder and march away, or maybe he’d hug the trunk of a bigger one, his kids grabbing the other end, and off they’d go. Lots of people from apartment buildings like ours have a tree so small they could tuck it under their arms and carry it home, but Dad doesn’t approve of those trees. “Dwarfs,” he says, “a poor excuse for a tree. You might as well bring home a twig or a stalk of celery.”

For us, this year’s tree is so big it has to come home by car. Paddy Power and Dad have it all roped up and hoisted up onto the roof of our old 1938 Plymouth and tied it down tight. I’m allowed to stand in the rumble seat to make sure it doesn’t move. “Jimmy, hold tight to the seat. If the tree starts to move, give me a shout.” Off we go, and I’m like a fireman on a hook and ladder or the lucky trash-man hanging on to the back of his truck. I cling to the seat with one hand and the tree with the other, but I’m able to give a quick wave to anyone who sees us go by. “You okay back there, cowboy?” shouts Dad.

When we get home, Mom and Joan have to come down to help us lug the tree up the flight of stairs to our place, apartment 2A.

“Joe, that’s an enormous tree, my God. Where in the name of God will we fit such a tree? Have you gone mad?” Mom inquires.

“‘Joe, take any tree,’ that’s what Paddy Power said to me, and so I’d say he was a shocked man to see the one we took. Isn’t that right, Jimmy? It’s one he could have sold to a bishop, but it’s here now, all ours. ‘Take any tree you want, Joe’ and so I took him at his word.”

And so we huff and puff our way up the stairs. Joan and I are as happy as Larry to have such a tree. In the days leading up to Christmas the apartment building becomes a forest of evergreen as people lean their trees on the walls outside their doors. If there’s no tree by a door, it must be the apartment of one of the Jewish families, or maybe a widow, or one of the atheists we heard about and prayed for in school, or maybe a Scrooge like Mr. Madden who lives in 3B and is always telling us kids not to play in the hallways on rainy days.

The ceilings in our apartment are high so our tree is always tall but this year’s tree is bigger than ever. Dad has to nail it down so it won’t topple over. Mom worries about the banging and the holes in the floor, but Dad says the rug will be put back down after Christmas and who’ll be the wiser.

“Joe Murphy, you’re mad about Christmas trees. Next year you’ll be drilling a hole in the ceiling.” Dad just laughs, “A good idea, Kathleen. Maybe 2A and 3A can share a tree. We’ll just send it on up through the floor to them. We’ll be like Rockefeller Center. What do you say to that?”

We all laugh to think of the Hurcombs up in 3A watching a tree poke up into their living room as we manage to make it stand and wait for Dad to cut the ropes. When he does, the branches spread like wings to nearly fill the living room.

“A redwood couldn’t match it,” he says with a big smile, proud as a peacock. On the Victrola, our cherished Bing Crosby’s “Merry Christmas” collection sets the tone. There are five of us and the album has five 78 rpm records so we take turns from oldest to youngest and stack up our choices on the turntable.

Jimmy, Eileen, and Joan and their dad, Patrick “Joe” Murphy on Christmas Day, 1948.

Dad picks “Silent Night,” then Mom takes “I’ll be Home for Christmas,” a hard choice for her since “Danny Boy” is on the flip side of that one, even though it isn’t a Christmas tune. I go for “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” instead of “Jingle Bells” on the flip side, and Joanie takes “White Christmas,” leaving my baby sister Eileen, who doesn’t know any tunes at all, with the only one left – “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen.”

Dad says, “Let the concert begin.” “Silent Night” fills the room as the tree awaits us. First, my baby sister Eileen is held up and we pretend she puts the star at the top of the tree. Then Dad and I begin with the lights, each of us on a chair since the tree is so high. We slowly work our way down, passing the string of lights from hand to hand. He reaches through all the wide branches to me, with my fingers searching for his on the other side of the tree.

Behind us, Mom and Joan unpack the ornaments, waiting for Dad to signal that we’re done and they can begin. Mom has two special ornaments, both from Ireland, and they are given a pride of place near the top of the tree – a crocheted star and a little cottage whose paint has chipped and dulled and whose chimney is missing. Once she has these placed on the tree, Joanie and I are free to add all the other ornaments and school cutouts wherever we wish. Then comes the finishing touch – the tinsel.

We hang a few tangled strands here and there on our own, but then we give way to Dad, as if by some unspoken signal. We don’t quite measure up when it comes to hanging tinsel.

It’s a special gift and Dad alone has it. His quiet patience, his silent introspection, humming as he works.

“Take your pick,” Paddy Power had said, and Dad had taken him at his word, so it was his tree. We all do our part to decorate it, but at heart it is his tree. He spends hours at it, a strand of tinsel at a time, absorbed in it as we all go off to whatever else calls us. But he stays there stepping back and looking at his work, correcting some of the chaos we’ve created in our clumsy tinsel efforts, a man at peace with himself. By now, we have heard all of Bing Crosby’s

Christmas songs at least twice, so our Irish records start to make their way onto the turntable, especially any one with a Christmas theme.

Because he works for Hostess Cakes and at Christmas he sells fruit cakes to one and all, Dad’s favorite is the McNulty Family singing “Miss Fogarty’s Christmas Cake.”

“Give us the Murphy Family version,” says Dad, and we all sing along with the McNultys, waiting to change the last line:

“There were plums and prunes and cherries, / There were citrons and raisins and cinnamon too, / There was nutmeg, cloves and berries / And a crust that was nailed down with glue. / There were caraway seeds in abundance / That would work up a fine tummy ache / It would kill a man twice after eating a slice / Of a Hostess Christmas cake.”

Mom’s favorite is “Christmas in Killarney” which, like “I’ll Be Home For Christmas,” makes her eyes fill up. “At home in Mayo,” she tells us, “It’s God’s truth what the song says, ‘The door is always open / The neighbors pay a call.’” Joanie and I like best when the song says, “And Santa Claus you know, of course / Is one of the boys from home.” But Dad says, “Santa’s not a Mayo man at all, he’s a likable, lovely Leitrim lad like myself.”

When we have everything all ready for the lighting, we place our manger at the base of the tree. We have Mary and Joseph, but no Baby Jesus because that’s Santa’s job when he comes on Christmas Eve. We have two shepherds but only two wise men. Dad says the third one must have followed the wrong star. “He’s like your Uncle Frank.”

Last come the animals, there’s a camel, a cow, and two sheep, all of them lying down. Mom says that’s because at home in Ireland all the animals in the fields would lie down on Christmas Eve to wait for the Baby Jesus. We have no fields or animals on Newkirk Avenue, so I picture the animals in Prospect Park Zoo. Come Christmas Eve, surely the lions and tigers and elephants and rhinos will all be lying down for the Baby Jesus.

When the stage is all set, Dad says, “Ready now? Close your eyes and count to three.” One, two, three, and we open. The tree fills the room with light, a waterfall of tinsel, and glistening ornaments. It is a Christmas tree of dreams.

“You know, Kathleen,” Dad says, “at home in Leitrim we didn’t have a tree at all. We hung some holly around the place, candles in the windows, but no tree. No room for one in small house with fifteen of us. So we settled for the holly and the ivy all over the place, just like in the tune.”

He winks at us. “No tree, but you know what, Jimmie and Joanie? Santa found us each and every year. At least we had a chimney for him. No chimney here in this apartment, but, by God, we’ll have a mighty tree for Santa when he comes.”